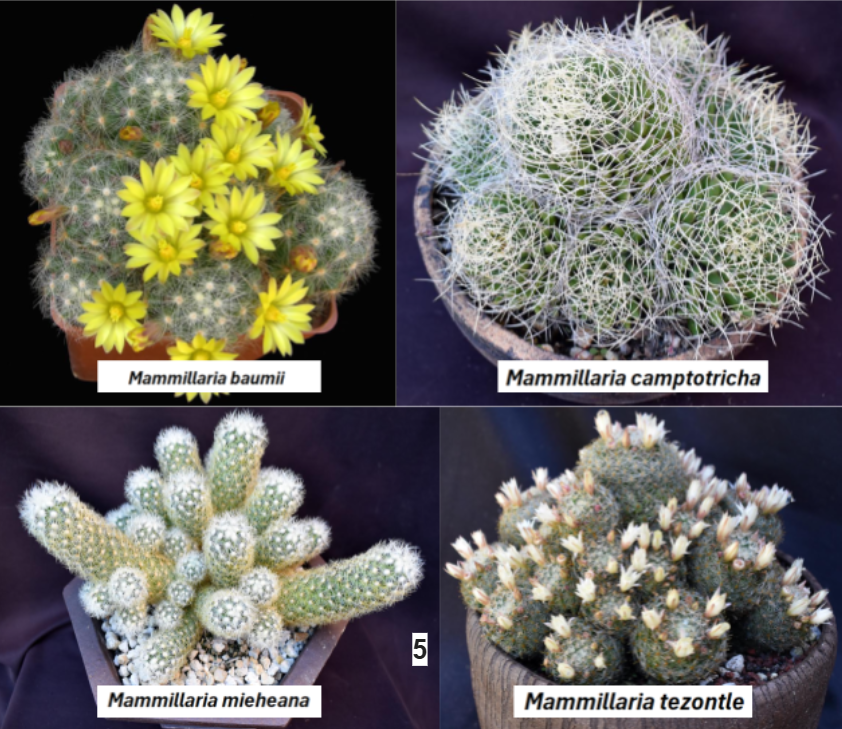

Cactus: Mammillaria clusters

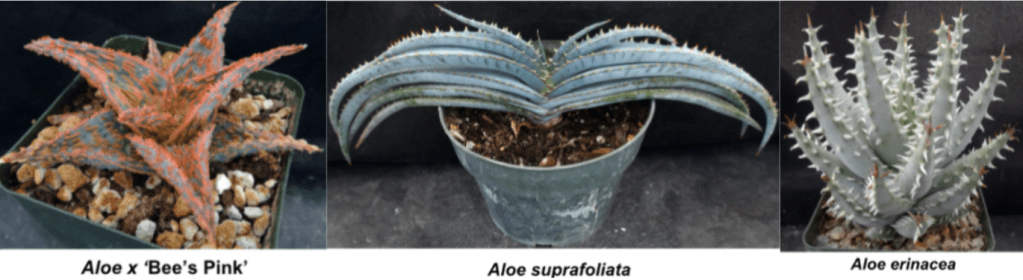

Succulent: Aloe

**Remember: You must be up-to-date on your membership dues to be eligible to compete in the monthly mini-show. See Jeff prior to submitting your plants to ensure you are current on membership.

‘Mammillaria Clusters’ by Tom Glavich (2025)

Mammillaria is one of the larger genera in the Cactus family and one of the most variable with some members remaining as solitary columns for their entire lives, some remaining as fingernail size solitary globulars, some clumped and heavily spined with hooks, straight sharp spines, or feathery soft spines.

Although most Mammillaria are native to Mexico, some species in the genus can be found from Columbia to Kansas and California. With this wide distribution the cultivation requirements obviously vary considerably. The species from the tropics and warmer areas are rarely tolerant of cold and damp. Those from the drier desert regions are also intolerant of continued damp but can take considerable cold. With these restrictions aside, most Mammillaria are easy to grow. The grower will have better success if they know where their plant is native to and treat them accordingly.

The secrets to good growth are a continued supply of fertilizer during the growing season, strong light, and maintenance of a clean and insect free growing environment. The white and densely spined species want full sun and do best on a table unprotected (except from prolonged heavy rain) all year long. The appearance of white mealy bug egg cases (Mammillaria’s worst enemy) on the tips of the spines or the appearance of ants means that mealy bugs are sucking the sap and life of the plant. Immediate treatment is required with thorough washing/ spraying with an insecticide and cleaning the remains off of the plant

Propagation of Mammillaria clusters is easy. Cuttings can be taken at any time during the growing season (April to October), left to dry for a few days and replanted in a clean potting mix (pure pumice is even better). Rooting is rapid with short white roots generally appearing after a couple of weeks. Mammillaria are one of the easiest species to grow from seed. The seeds are simply placed on top of a damp potting mix, covered with a light coating of gravel, placed in a plastic bag in bright light but out of direct sun and allowed to germinate. Germination usually occurs in a week or 10 days. The seedlings can stay in the plastic bag for several weeks until they get large enough to survive unprotected and should then be removed to a still shaded, but brighter and drier environment. Show quality plants can often be grown in just 4 or 5 years and entries can be ready for seedling classes in as little as 6 months. Best results are obtained when the seeds are planted in late March to late May.

Clumping Mammillaria

Mammillaria baumii is a densely spined species with wonderful large yellow flowers. It is easy to grow and makes an impressive specimen in a modest size pot. It comes from Tamaulipas, Mexico

Mammillaria crucigera produces clumps by splitting dichotomously (each head splitting into two). The body ranges from green to almost brown to almost purple. This species is a slow grower.

Mammillaria duwei is from central Mexico. At first it is slow to pup, but persistence and patience pay off.

Mammillaria elongata, one of the first cacti that everyone grows is easy and extraordinarily tolerant of abuse. It has the odd characteristic of being very popular and also unfairly neglected since advanced growers ignore this easy grower even though there are a variety of forms and colors many of which can make a spectacular plant.

Mammillaria geminispina, is a variable species with some varieties having short white spines while others have long flexible centrals.

Mammillaria herrerae is a spectacular small white species with very dense interlacing spines. It comes from Queretaro Mexico.

Mammillaria lenta, from Coahuila forms mounds of off-white to white. Slower growing than the somewhat similar M. plumosa, described below, it is often a show winner.

Mammillaria luethyi from Coahuila and discovered in 1996 is now available in cultivation. A breathtaking miniature with very short white spines on a dark green body.

Mammillaria plumosa is a relatively quick grower forming mounds of white heads. The heads are covered with white feathery spines which must be kept dry if the color is to be maintained.

Mammillaria standleyii can be found as either a single or clumping species. In cultivation, clumping forms are much more common. It is a rapid grower.

‘Aloe’ by Kyle Williams

Aloe is one of the most popular genera of succulents, especially in Southern California. In fact, Aloe vera may be the most widely cultivated succulent in the world, owing to its medicinal properties. Most species are small herbs to shrubs, though some species (most notably A. dichotoma and A. barberae) can reach tree size. With over 500 species, and at least as many hybrids and cultivars, there is an Aloe for almost any situation and taste.

Aloe species are native to most of the drier parts of Africa, including Madagascar, with a number reaching the Arabian Peninsula. They are naturalized in every Mediterranean environment in the world, as well as some temperate and tropical regions. All but a few Aloes will grow readily in Southern California, either in the ground, or in pots.

When in the ground they require minimal care, existing happily on only natural rainfall in most years. Summer growing species will appreciate some summer water. The sheer number of species and habitats make blanket statements on culture impossible, but most will thrive under the general care you give other succulents, so long as you know if you have a summer or winter grower.

Aloe combines interesting form and foliage with beautiful flowers. Most species have orange, yellow, or red flowers that are attractive to Sunbirds in their native Africa. In the Americas hummingbirds regularly visit them. These birds are great at pollinating flowers, and it isn’t unusual to see fruit develop. Those looking for other colors can find species with white or even green flowers. Some species, such as A. tomentosa, even have hairy flowers! Given that Aloe is such a large and diverse genus it may not surprise you that modern taxonomic studies are showing that some Aloe species are best split off into distinct (but still related) smaller genera. The reason for this isn’t just to make life more difficult for you! A genus should contain only species that are more closely related to each other than any are to species outside the genus. When we find out that some species in a genus are more closely related to species outside the genus taxonomists have two choices. Either you combine everything into one big genus, or you split the problematic species out of the genus. DNA research has shown that if we want to keep all the species we currently think of as Aloe in the genus Aloe then we have to put a bunch of other species in the genus as well. That doesn’t just mean a couple obscure species no one has ever heard of. Instead, it would require putting all of Haworthia and Gasteria (among others) into Aloe itself.

If you want to keep Haworthia and Gasteria as their own genera (though they have their own issues we won’t discuss here) then you have to be willing to split out a few Aloes from Aloe. Thankfully the vast majority of traditional Aloe species are still in Aloe and less than 20 species have to be removed from the genus. The most notable segregate genus is Aloidendron which are easy to recognize as they constitute 6 tree or shrub species including A. barbarae, A. dichotomum, & A. ramosissima. The largest segregate genus with 10 species is Aloiampelos which tends to be shrubby or climbing species. The third genus Kumara was created for the well- known Aloe plicatilis (now Kumara plicatilis) and one other similar species. For the sake of our Plant of the Month show you can submit plants from all four “Aloe” genera: Aloe, Aloiampelos, Aloidendron, and Kumara.